"T2D3 or Triple-triple-double-double-double", penned in 2015, is the standard baseline metric that most software venture capitalists use to determine if a SaaS startup's growth trajectory merits investment. Similarly, it has become the yardstick that SaaS startup founders use to measure their own progress and guide their fundraising strategy.

For those not familiar with the concept, it goes something like this - once a company gets to $2M ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue) it should grow as follows:

Next Year – Triple: $2M to $6M ARR

Next Year + 1 – Triple: $6M to $18M ARR

Next Year + 2 – Double: $18m to $36M ARR

Next Year + 3 – Double: $36M to $72M ARR

Next Year + 4 - Double: $72M to $144M

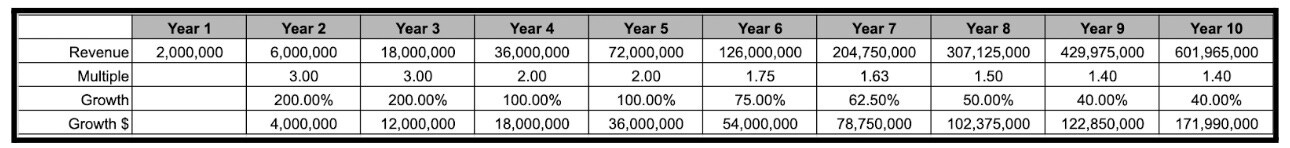

And then voila, your company is off to the races and world domination. A general 10-year forecast (or nine years after $2M) may look like the following:

Traditional T2D3 Model

I have adjusted growth rates after Year Five simply because growth does indeed tail off for most T2D3 adherents. Unless the company unlocks major product revenue expansions, it is tough to grow more than 50% when you are north of $100M in ARR.

From an investor's perspective, this baseline allows them to:

filter for only the best investments to consider in the least time needed

more easily pay aggressive ARR multiples for companies, assuming that the growth and its premium will continue for later round raises

pressure-test founders early to see if they can drive terrific growth

understand in existing investments if there is a natural market pull for the company and, if not, more easily guide the company to a safe landing through an M&A exit.

Make no mistake, top line growth for software companies is the fundamental driver of value creation.

All else being equal, companies that grow faster are worth more. However, in a post zero interest rate period (ZIRP) world, founders must now be very conscious of the capital they are consuming to get to $2M in ARR and some real proof of product market-fit and the capital they are consuming to grow impressively post $2M in ARR.

I do advise founders at the $2M to $3M range to pursue this approach IF the business momentum is there to do so rationally. If, as a founder, your go-to-market efficiency is excellent (magic number is => 1, and your burn multiple is not egregious (<= 2), then absolutely go for it. Similarly, if 1+ your growth rate > burn multiple, follow the T2D3 path.

However, if your GTM motion is AE capacity-driven, and you are not hitting those metrics above, you should be very careful about using the T2D3 model as your performance yardstick, especially when approaching the $2M ARR mark.

I believe this investment criterion for what has defined "great investments" can create a very unhealthy mental model for most software founders when they are sub $10M in ARR for the following reasons at a summary level:

1 - The Math is Shortsighted: 5 Doubles Gets you to $100M

2 - It Sets Capital Raises as the Core Goal for Founders

3 - It is Extremely Risky to Chase the First Two Triples

4 - It May Force Founders to Grow Faster as Leaders than They Can

5 - It Does Not Provide Founders Enough Time to Make Mistakes

6 - It Can Ironically Affect a Founder’s Ability to Think Bigger

7 - It Delays Financial Discipline for Far too Long

8 - It Blows Up Companies Prematurely if They Miss the Bar

9 - It is Not a True Sign of Companies that are Built to Last

Note: Most of the VC world has moved the goal post for when to apply the T2D3 model to considerably earlier ARR multiples - i.e. did a company triple from $300K in ARR? For many of the same reasons outlined below, this is even more dangerous and does not buy founders the time to explore / iterate enough to ensure they really have “something” that it makes sense to lean into capital wise.

Let’s get into it:

1- The Math is Short-Sighted

As a seed investor, we have a 10-year exit horizon. VCs do need to see a feasible path to $100M in ARR within that time frame for us to invest. $100M in ARR in "normal times" for a business growing >40% and attractive efficiency metrics would usually drive a 10x multiple or a $1B exit. For more reasons as to why we as investors have to believe that in order to lean in, chat gpt tells us more:

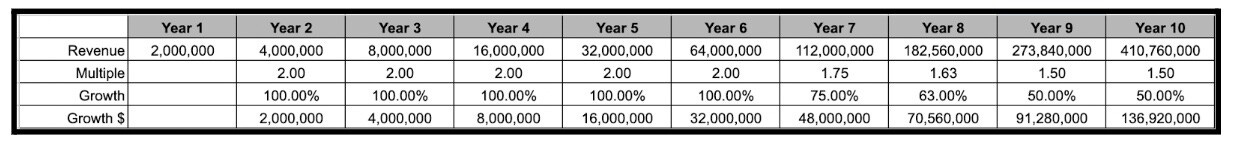

That being said, the T2D3 math model ignores one simple fact - over ten years: a D5 (double for five straight years) gets you to $100M, no problem. As an example, see below:

Alternative D5 Model

I still show a double in year 6 as the relative absolute growth number is easier to achieve. Of course, it's always better to capture the genie in a bottle and deliver a T2D3. But few founders and companies do so and end up tripping and falling badly along the way.

I would argue that the companies that pursue the T2D3 model dogmatically see more significant drops in growth over the years as the laws of large numbers still apply and, in their pursuit of early explosive growth, they did not give themselves the time to ensure they were:

- building a long term cash efficient business

- establishing deeper product market fit

- launching sustainable act 2 product lines to expand their TAM

- avoiding increased churn due to selling to too many poor fit customers

Interestingly, we have several examples of companies in our portfolio whose growth actually accelerated as they passed $10M in ARR as they took the time, energy, and hard calls to build a "balanced house" that becomes a juggernaut. So indeed growth matters, but not necessarily so early in your journey.

2 - It Sets Capital Raises as the Key Goal for Founders

The T2D3 model leads founders to overly focus on the goals they must hit to successfully raise additional rounds of capital. It unnecessarily distracts founders from thinking through what core business goals they must accomplish in order to achieve that growth. Instead, it encourages top-line ARR growth, sometimes at all costs - i.e., "I must grow this fast to be able to raise again."

That top line number is an output of hopefully really important inputs like: Where is your product in 24 months? How much more/better do you solve the "jobs to be done" by your audience? What are the core gaps on your team that you have to fill? How do you reduce CAC and improve marketing and sales conversion rates? What economic efficiency model do you want to prove in your GTM approach? And so on.

Unfortunately, if founders focus too much on an ARR goal as the input to next-round success as opposed to the output of solving for the small subset of inputs founding teams have to get right, things often get squirrely fast.

3 - It is Extremely Risky to Chase the First Two Triples

If you are a SAAS startup in 2023, it is a dramatically different landscape than 2015 when there were just a handful of SAAS companies selling to each core target buyer in an org. Today, there are 100 x as many vendors chasing each of those same buyers using the same playbooks. As such, go-to-market is far more expensive and breaking through the noise is far more difficult today.

Breaking through that noise and ensuring your product value proposition resonates is damn hard and takes time. So, aside from being careful about which waters your startup is fishing in, understand the existential risk of chasing your two triples. At $2M in ARR, if your business growth is tied to how much future effective quota capacity you need, you must invest capital considerably ahead of time without often having the confidence that investing those dollars will bear fruit.

Does this story seem familiar? A founder gets to $2M in ARR with primarily founder-led selling and then, to hit two triples, follows the “playbook” and goes on a massive GTM hiring spree with a CRO, lots of AEs and SDRs. However, the company usually has yet to finalize product market fit nor build repeatable pipe gen & sales processes. They then hit a wall somewhere in the 3rd quarter of that first “go for it” first year and their burn rate skyrockets as their growth slows. The founder then has to let a bunch of people go and resist the urge to look at glassdoor where they are getting just eviscerated.

I am not against investing in incremental capacity, but the capital you have raised is expensive, and you need to be wise about where and when you spend it. The odds of large incremental bursts in GTM spending paying off so early in your journey are low. For 98% of start-ups, it is extremely expensive to chase 3x so early in a world where follow-on capital is far more scarce and applied with far more scrutiny.

4 - It Forces Founders to Grow Faster than is Naturally Normal as Leaders

Growing from $2M to $18M in two years generally means that a company’s headcount balloons from 20 to 150 or so employees. This means that a founder must transition quickly from managing a scrum team of ICs to managing a set of cross-functional leaders who manage directors who manage ICs. This transition is extremely tough for founders, especially if they are a first time founder and especially if they are younger and have no prior employee management experience.

Founders have to know when to remove themselves as a bottleneck. They have to know when to deep-dive and when to delegate. They have to know when to trust their gut vs the experience of a newly hired VP. They have to know when to find the right balance in communicating to their employees company progress versus shortfalls. It's damn hard.

Companies can only grow as fast as their founders grow in their leadership ability. So unless the business is on complete fire and you are a natural-born leader who has figured this all out, perhaps consider slowing down a bit.

5 - It Does Not Provide Founders the Time to Make Mistakes & Adjustments

My favorite quote that I have used through my 25 years in software (as an operator or an investor) is the following from Mark Twain:

"Good judgment is the result of experience, and experience is the result of bad judgment."

We only truly learn when we try things that do not work. As a kid when you put your hands on a stove, you built deep institutional memory to never do that again. At your first $2M in ARR, you still know very little about your company, market, buyers, and competitors. If you aim to get to $100M in ARR, you are only 2% along your journey. You don't know sh$#, and that's fine. As a comparison, if the average life expectancy for an American is 77 years, we surely wouldn't expect much world insight from a 18-month-old.

The journey for a founder from day zero to $2M in ARR requires unlimited resilience and grit. Every day and week is chock full of nos and failures. You want to throw a pizza party when you get just one yes. Even one of the best entrepreneurs of our generation recently stated if he knew now what it would take to succeed, he wouldn’t have founded Nvidia. There is no set of blogs or online playbooks (often written by people who have never done anything significant) that you suddenly just put into action. You must develop a thesis and go through innumerable trials and errors to see what works and what does not. The outcomes from these efforts deliver the real aha moments that form the basis for repeatability.

At $2M - $10M in ARR, you are working to transition from what worked for you and a handful of customers and employees to an approach that can scale repeatedly. Nailing repeatable market-fit and repeatable operational processes takes time - and you will only get there by making mistakes and adjusting appropriately. As such, give yourselves the proper time to do so. If you try to go too fast, you can miss critical lessons, which could torpedo your business later.

6 - It Can Affect A Founder's Creativity and Ability to Swing Big

Ironically, strict adherence to a T2D3 model can close off an opportunity to build a more impactful company. When founders try to hit triples early while investing capital uncomfortably, it dramatically increases their "pucker" factor. It creates an almost unimaginable deal of mental stress. Founders often already deal with some impostor syndrome, and going for two triples just dials the pressure to a level 10. If you are a founder, ask yourself what type of sleepless dream you routinely have. It is usually some form of a "missing a math class ." My version as an early stage executive was as a lead actor on Broadway where I was naked and forgot my lines. As such, under this pressure, it's almost impossible for a founder not to close off somewhere in their brain some mental flexibility/problem-solving space.

The space that allows you to rise from the daily grind to work on the business and not just in the business. The space that allows you to ask yourself - are we selling to the right customers? Are we building the right product? Are we marketing or selling it the proper way? Are we building a long-term economic model that will make sense? Founders need the time to ask themselves these questions and tweak/adjust or, sometimes, completely pivot.

The most successful SaaS CEO ever once told me when I was being, in retrospect, short-sighted, "Don't overestimate what you can accomplish in a year. More importantly, never underestimate what you can do in a decade." If you feel you need to hit two triples in a row, you often feel like you have to stick to "what you are doing," focus on the here and now and ignore the proper adjustments for the mid and long-term that are key to your company becoming an iconic one. Especially if you are concerned that you will surprise/let down your investors who chose to believe that everything was on track.

7 - It Delays, Often Forever, Financial Discipline & Constraint-Based Thinking

For a founder, chasing a T3D2 in your early days will inevitably pull you farther and farther away from constraint-based thinking. The T2D3 model encourages you to do what every other VC-funded startup is doing - hire aggressively across your company to ensure you have the capacity to deliver two triples . You tell yourself it's okay because the model spits out terrific top-line growth and incredible magic number and burn ratio metrics.

But in the end, businesses need to make money, and a CEO's top job is to be a great steward of capital – you have to deliver the right mix of growth and EBITDA over the longer term. You need to invest your money where it provides the highest return, i.e., pursue customer segments with the highest LTV/CAC. That, in the end, are the markers of great businesses.

Leaders need to adopt a constraint-based approach to investing capital in today’s market. It's not an AND world - i.e., I need these reps, and I need these marketing dollars, and I need these developers, etc. It is an OR world - given my priorities, how do I make a hard call on what to invest in and what not to? I have seen far too many T2D3 companies start to struggle around year 5-6 when growth rates dip below 100% with cost structures that are upside down as they were predicated on infinite terrific growth. When these companies need to adjust, make hard calls, and move from an AND model to an OR model, it takes way too long for them to change their cost structure, culture, and decision-making process to reflect the reality of the world of slower growth.

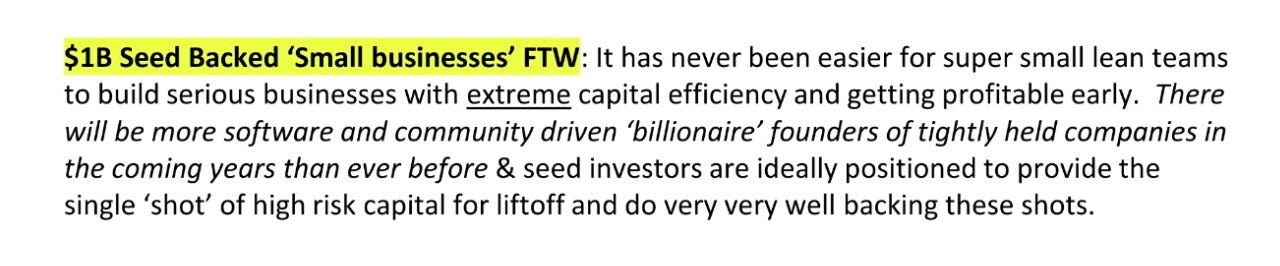

The exciting reality around not just the impact of AI but the commoditization and inexpensive availability of 90% of the software stack is that founders with great ideas and terrific execution can build massive, impactful companies with far less capital than what one once needed a decade ago (salesforce.com, for example had to build and run all of its own data centers for years). Raise less, deliver more, and own more of your company. Don't believe me - see what Sam Lessin just put out:

From "WTF VC - Fall 2023"

8 - It Blows Up Companies Prematurely if They Miss this Bar

Software startups are incredibly risky endeavors. An infinitesimal number of companies go public. Less than ½ of seed stage companies make it to Series A. As such, very few companies nail the T2D3 model. Unfortunately, when founders miss that benchmark, they mistakenly view themselves as "failing" - especially if they consumed all their capital prematurely before product market fit and proper repeatability.

The reality is that you might not be on to something afterall. Similarly, you might be an excellent company with a compelling product. You might be in a market, i.e., a vertical industry or a brand new category, where sometimes you are creating and bending the demand curve and can't outspend it so early. You may have tried to do too many things in too little time and burned too much capital during your key trial and error period.

The T2D3 model would instead have you believe that you need to raise more money - at a steep discount to the last round and suffer colossal dilution. I would recommend that you get your company to cash flow break-even, decide if you are still passionate about the opportunity and live to see another day. Or better yet, avoid this outcome from the get-go.

9 - Finally, and Most Importantly, it is Not a Sign of A Company Built to Last

For companies that go public, 90% of their value creation occurs after year 11. In the public markets, investors are now looking for the right mix of top-line growth and profitability/ability to throw off cash. For companies that don't go public and have an exit, it is through an acquisition - from either a strategic or through private equity.

In the case of a strategic acquisition, unless you have substantial revenue and go-to-market teams, acquirers care most about the quality of your product and how easily their go-to-market teams can sell it. For those with substantial revenue, acquirers will want to ensure that your P&L fundamentals are attractive enough not to drag down their combined results once the acquisition is complete.

For a private equity buyer, they care most about 1) your ability to spin off cash in the future (i.e., the rule of 40) to service debt levels and 2) the likelihood of pairing your offering up with other companies in their portfolios to create more prominent combined companies. If you want to create more optionality as a founder, pursuing a more capital efficient D2D3 model allows you to be both attractive to PE and Strategics at the same time.

In both acquisition scenarios, no one cares if you did two triples out of the gate. In fact, they often prefer you did not, as that implies you may have raised a ton of capital, which will force them to increase their bid prices to get all of your preferred investors on board.

So if not T2D3 – then what?

So, as a founder who started their businesses because they couldn't imagine doing anything else and who couldn't stomach their product not existing, ask yourself the following:

Is this T2D3 model right for you? If you have a tiger by the tail and there is real market pull for your product, your sales efficiency and retention metrics are top-notch, and it feels easier to go for those first two triples than not, then, by all means – go for it. But if not, is this the way you should measure your achievements so early in your journey? Is this the way you want to spend your hard-earned investment dollars? Is this pressure worth it?

An analogy to consider: is T2D3 any different, especially for first-time founders, than asking someone to run 6 minutes miles on a treadmill forever without breaks? And while they are at it, please wear these rubber duckie shoes while someone pours oil on the treads . Run, founder, run but don't fall!

Consider, if you will – a more straightforward model – a D5 Model instead of T2D3 model with far better cash efficiency and more time and data to make the right constraint-based decisions to build a solid company foundation.

Take that time to find great product market fit and generate natural market pull. Ensure that you have high quality customers that aren’t non ICP or flighty during downturns. Build real customer love and community - one of tech companies' only real defensible moats, IMHO. Build a repeatable demand generation strategy. Develop a set of repeatable plays in sales. Nail how best to deliver customer success and drive high NRR. Feel free to set annual high-level objectives, but run your company quarterly to ensure you regularly reflect on progress and make appropriate pullback or incremental investments.

And then, once you have that stable base and start to feel actual market pull - feel free to go for even higher growth rates as you are now more comfortable with where to place your cash. Maybe, just maybe, you get to $8M in ARR on $10M in total capital raised - which is far healthier than someone who hits two triples but spent $40M to get to $18M in ARR.

And yes, though it may not garner a Series A / B valuation as high as a business with higher growth, there are investors NOW who appreciate a more balanced approach to growth versus capital consumption. Christophe Janz of Point 9 Ventures presented at SaaStr the results of a survey that showed that YTD the average Series A recipient grew 120% (2.2x), demonstrating that it's not 3x or bust these days.

Because in the end, remember, if your company is still in business in a decade, who cares about whether you tripled or not in your first few years after you hit $2M in ARR? I don't.